About Fatema Mernissi

Fatema Mernissi was born into a middle-class family in the Moroccan city of Fez in 1940. She attended Quranic school where she received her primary education in a school established by the nationalist movement, and secondary level education in an all-girls school funded by the French Protectorate. As Mernissi pointed out herself, she belonged to the generation of women in Morocco who benefited from the educational policies of the post-independence Moroccan nationalist government.

Mernissi received a degree in political science from Muhammad V University in Rabat, Morocco, in 1965; she continued her education at the Sorbonne in Paris, where she also worked for some time as a journalist. In 1973, she received a Ph.D. in sociology at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, USA, for her dissertation The Effects of Modernization on the Male-Female Dynamics in a Muslim Society. She returned to work at the Muhammad V University and taught at its Faculté des Lettres between 1974 and 1981 on subjects such as family sociology, methodology, and psychosociology before being appointed Professor in Sociology. Mernissi also held an appointment as Researcher at the Moroccan Institute Universitaire de Recherche Scientifique. In addition, she was a visiting scholar at numerous universities and colleges in Europe and in the USA.

With Hillary Clinton

Fields of Activity: Fieldwork and Writings

Felipe VI, King of Spain, presenting the Asturias Award

in 1975, Mernissi published her first book, BEYOND THE VEIL: Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society. Based on her Brandeis PhD thesis, it has become a classic, especially in the fields of anthropology and sociology of women in the Arab World, the Mediterranean area, and Muslim societies in general.

As an Islamic scholar, Mernissi was largely concerned with Islam and women's roles in it and in helping to create civic society. Through a detailed investigation of the nature of the succession to Muhammad, she cast doubt on the validity of some of the hadith (sayings and traditions attributed to him), and therefore the subordination of women that she saw in Islam, but not necessarily in the Qur'an.

As a sociologist, Mernissi primarily did fieldwork in Morocco. Interviews with Moroccan women of different ages, different social classes, and different walks of life were presented in her book LE MAROC RACONTÉ PAR SES FEMMES (1983), revised and republished as PAROLÉS DES FEMMES DU MAROC (1991); it was published in an English translation as DOING DAILY BATTLE (in Britain 1988 and in USA in 1989). She also did sociological research for UNESCO and ILO.

In the late 1970s and in the 1980s, Mernissi contributed articles and essays to periodicals and journals on women in Morocco and women and Islam more generally from a contemporary as well as from a historical perspective. For example, she published articles in the women’s studies journals Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, Women’s Studies International Forum and Feminist Issues. Her contribution about women in Morocco to the anthology SISTERHOOD IS GLOBAL, edited by the American feminist activist Robin Morgan (1984), is noteworthy in this connection. The anthology provides statistical information on women in 70 countries, arranged alphabetically, in most cases supplemented by articles of various length.

Mernissi’s first book, BEYOND THE VEIL: Male-Female Dynamics in Modern Muslim Society, was based on her PhD thesis for Brandeis and was first published by Schenkman in 1975. A revised edition was issued in Britain by Al Saqi in 1985 and in the USA by Indiana University Press in 1987. Al Saqi published a further revision – with a new introduction by Fatema Mernissi – in 2014. BEYOND THE VEIL has become a classic around the world, especially in the fields of anthropology and sociology on women in the Arab Word, the Mediterranean area, and the Muslim world in general.

In her writings, Mernissi sometimes refers to LA FEMME DANS L’INCONSCIENT MUSULMAN by Fatna Aït Sabbah, originally published in 1982, and translated into English as WOMAN IN THE MUSLIM UNCONSCIOUS (1984). Aït Sabbah, a pseudonym for a ‘Muslim woman scholar’, analyzes perceived intertwined Muslim erotic and legal discourses in order to, in a Foucauldian manner, “decode the messages that the Muslim cultural order has tattooed on the female body,” influencing the contemporary Muslim understanding of femininity and politics. The book contains references to BEYOND THE VEIL. Toward the end of her life, Mernissi acknowledged being the pseudonymous author of WOMAN IN THE MUSLIM UNCONSCIOUS.

When Fatema Mernissi is referred to in the context of gender egalitarian or feminist interpretations of Islam however, it is her two books, LE HAREM POLITIQUE (1987) and SULTANES OUBLIÉES(1990) that are usually mentioned. The former was translated into English in 1991 as THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE: A Feminist Interpretation of Women’s Rights in Islam in the USA. (The British publisher called it WOMEN AND ISLAM: An Historical and Theological Enquiry.) THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE was initially banned in Morocco. SULTANES OUBLIÉES was published in an English translation in 1993 under the title THE FORGOTTEN QUEENS OF ISLAM.

Both these books are historical in scope. The former relates mainly to the history of Muhammad, and the latter presents and discusses women in Muslim history who have held political power, primarily those whose sovereignty was officially recognized. Muslim history, or rather Muslim historiography, is also partly the topic of the book LA PEUR MODERNITÉ: Conflit Islam Démocratie (1992), translated into English in 1993 as ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY: Fear of the Modern World (now also the title of the latest French edition). Historical information here is related in a more general discussion on the post-Gulf war Arab and Muslim world, and especially to the question of democracy, political power, and civil society.

Mernissi’s only novel, DREAMS OF TRESPASS (or THE HAREM WITHIN in the UK edition), was well received around the world, with translations published in 28 different countries. It was originally written in English. While autobiographical in style, Mernissi always presented her book as FICTION - a novel inspired by, but not describing actual events and persons. Mernissi wrote and published 9 other books.

Throughout her literary career, Mernissi often used the terms ‘Arab’ and ‘Muslim’ interchangeably. She discussed this usage in a footnote in ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY and also explained it elsewhere: that Islam was originally expressed in the Arab language, and that Arabic still is the sacred language of Islam. This is why she concentrated on an Arabic-Islamic terminology in her attempts to map a ‘mental territory’ common to a larger Islamic civilisation.

When Mats Svensson in 1993/94 wrote a concluding essay in Islamology on ‘feminist’ reinterpretations of Islam, he noticed a difference between Mernissi’s writings on Islam and women in BEYOND THE VEIL and the later THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE. The change was evident for example in her presentation of al-jhilıya. While changes brought about by Islam were evaluated negatively in relation to women’s situation in al-jhilıya in BEYOND THE VEIL, the reverse was the case in the later book. He connected this change to what others had noted as a wider trend among feminist activists in the Muslim world during the 1980s. In order partly to legitimise their activity, and partly to mobilise wider social support, feminists who earlier had taken an indifferent or even polemic position in relation to the religious tradition, had increasingly begun to actively make positive use of Islamic normative material.

All Mernissi’s books and articles have been published in the Mahgreb, Europe, or in the USA, some with a European and American academic and mostly non-Muslim public as the primary audience. But there are also companies and feminist organisations in Muslim countries that have published her work. In Pakistan for example, the socialist-feminist ASR Resource Centre for Women, set up in 1983, published a version of FORGOTTEN QUEENS OF ISLAM, while Éditions le Fennec published a French version in 1990, as well as French and Arabic versions of a number of other books. Mernissi describes Layla Chaouni, the long-time Publisher of Éditions le Fennec in Casablanca, as ‘committed to the struggle for human rights’ and notes her help in the production of books and collections from local research collectives.

Mernissi and her writings became known worldwide and she was much sought after as a visiting scholar, participating in numerous international, regiona, or national conferences on issues such as women and Islam, women’s situation in the Muslim world, development, democracy, civil society building, globalization, North African immigration to Europe, and world literature.

Human Rights

Mernissi was one of the founding members of the Moroccan Organisation for Human Rights. She often referred to ‘human rights’ in general and also to specific articles of the UDHR (United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights), citing international formulations of human rights as products of historical circumstances peculiar to ‘The West,’ with a philosophical basis in the ideas of the Enlightenment, in liberal thought, and in general trends connected with modernity. She presented certain basic principles as inherent in the notion of human rights: parliamentary democracy, equal rights as a result of citizenship, freedom of thought and speech, freedom of religion, and secularism understood as the separation of religion and state. In the center stood the notion of the sovereign will of the individual.

The legal aspect of ‘human rights’ was stressed in ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY where UDHR and the United Nations Charter are described as ‘superlaws’ that override national laws and constitutions. She attributed the problem of realising human rights in Arab/Muslim societies partly to the fact that human rights were not accepted as a result of a general social transformation in line with modernity.

In Mernissi’s writing in general, however, there is little elaboration on the issue of universality of human rights and cultural relativist critique, and likewise on the relationship between the Islamic normative sources and international standards of human rights.

In THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE, she writes in connection with a discussion of the piecemeal character of traditional fiqh that:

We can imagine, or dream, that an elaboration of a system of fundamental principles [as opposed to the stress on particulars] would probably have allowed Islam as a civilization of the written word, to come logically to a sort of declaration of human rights, similar to the grand principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a universal declaration that still today is challenged as being alien to our culture and imported from the West.

Women’s Human Rights: Connecting Women’s Rights with Human Rights

In THE FORGOTTEN QUEENS OF ISLAM, Mernissi writes that it was ‘obvious to fair minded people’ that there is a link between ‘rights of man’ and the non-violation of those of women. She also stressed the importance of the UDHR for activism in the area of family law in ISLAM AND DEMOCRACY. She specifically addressed Egypt’s reservations about Article 16 as ‘double talk’ and as lacking in clarity, writing that it showed how ‘Arab states’, given the realities of international politics, could not openly reject the principle of equality, so that Egypt’s reservation was a ‘loophole’ in which religion was hypocritically manipulated.

Mernissi highlighted gender specific problems in areas such as work, education and law in discussions regarding women’s human rights. Likewise, she specifically addressed the issue of veiling as state policy. In her introduction to BEYOND THE VEIL, the Moroccan Code of Personal Status, the Mudawwana, is posed against articles 16 and 29 of the UDHR. The issues mentioned are the rights and duties of the husband and wife within the marriage, the necessity of a walı, and inter-faith marriages. In THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE, she highlighted the mudawwana’s stipulation of the husband as the director of the affairs of the family is and contrasted it with Article 1 of UDHR.

In BEYOND THE VEIL, conflicts such as these were treated as a symptom of a larger problem. She saw Moroccan legislation mirroring and reproducing traditional, as opposed to modern, concepts of gender, and considered these concepts to be in conflict with actual changes brought about by modernisation in fields such as education, employment and public life in general, as well as in patterns of gender relations and the family. The result was a ‘confusion of norms’ experienced primarily by younger people. She regarded change in legislation as being further impeded by the symbolic charge of the notion of a Divine law.

In this connection, Mernissi wrote about women’s paid employment as challenging traditional ideals of the sexual division of labor. According to those ideals, the public space was the area of production and the private space the area of consumption and reproduction where the man served the role as provider of women. In later essays, she attributed the failure of state sponsored programs in Morocco on reproductive rights to state interference within the private sphere. Mernissi maintained that women’s political rights were hampered because of this gendered separation of public and private.

In BEYOND THE VEIL, both the origin and the endurance of the separation of public and private are connected ideologically to Islam. An important concept in this connection was the umma. The umma is male, egalitarian, united on the basis of common belief, characterised by love and the center of public activity. It is opposed to the family, which is characterised by its femaleness, its inequality and its diversity. The members of the family are divided into two antagonistic categories defined by their sex and related to one another in a hierarchical system of authority and subordination. The principle of female obedience is central. In later writings, Mernissi stressed the basic notion of stability, coherence and consensus within the umma as an ‘Islamic’ social ideal, an ideal that was threatened by plurality.

The Ideal and How to Achieve It

Women’s full access to public life, implying the eradication of the public/private distinction, was important to Fatema Mernissi.. Women should be regarded as full citizens, which included equality before the law. Discrimination in fields such as work, education, and health must be ended. The word ‘democracy’ figures abundantly in Mernissi’s discussions of women’s rights, specifying the concept in some contexts more clearly as parliamentary democracy and connected to universal suffrage.

In THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE, Mernissi made a clear distinction between religion as a personal belief and religion as law. In an explanatory remark regarding how she uses the expression ‘we Muslims’ in describing the contemporary situation she wrote:

The expression does not refer to Islam in terms of an individual choice, a personal option. I define being Muslim as belonging to a theocratic state. What the individual thinks is secondary for this definition. Being Marxist or Maoist or atheist does not keep one from obeying the national laws, those of the theocratic state, which define the crimes and set the punishments. Being Muslim is a civil matter, a national identity, a passport, a family code of laws, a code of public rights.

In 1996, Mernissi presented her investigation into Islamic history and dissemination of information as a way of ‘standing up to fundamentalism’, and of identifying ‘women’s autonomy as an endogenous phenomenon.’ She stressed the importance of Muhammad and his companions in the contemporary discourse on women’s rights and Islam In articles and essays published after THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE, Mernissi claimed that the historical sources themselves provided enough material to substantiate a claim that ‘women’s passivity, seclusion and their marginal place in Muslim society had nothing to do with Muslim tradition and was, on the contrary, a contemporary ideological production.’ Alternative models of femininity could be provided by the historical sources, and these models could in turn be used to confront accusations against feminists of importation of ‘Western’ models and ideas.

Self-presentation

Mernissi often used inclusive expressions such as ‘we Muslims’ or ‘we Arabs’ and presented herself as a ‘Muslim woman.’ She also described herself as being Berber by ethnicity, like most Moroccans. Against this inclusive tendency stands her acknowledgment e that she, and other highly educated women, are, or rather are perceived by others to be, somewhat distanced from those women they write and speak about. The class perspective is often explicit, even though she held that differences in this respect can be overcome. In this context, Mernissi suggested that an educated elite could be a vanguard in the general aspirations for change in the modern world since it had important access to modern media, especially television and the web.

Mernissi appeared to have little problem with the term ‘feminist.’ In connection with an explanatory exposition on the Arabic term Nisa’i and various alternative renderings of the term feminism in Arabic, she wrote:

Nisa’i is for me an adjective that designates any idea, project, program, or hope that supports women’s rights to full-fledged participation in and contribution to remaking, changing and transforming society, as well as full realization of one’s own talents, needs, potentials, dreams and virtualities. And it is in this sense that I have always lived and defined women’s liberation, whatever the language – ‘feminism’ or nisa’ism.

Mernissi’s references to personal experiences as a basis for activism are concentrated mainly in THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE and essays and books written after 1987, such as SCHEHERAZDE GOES WEST.

Mernissi’s personal experiences were important also in relation to her interpretation of religious texts. In her introduction to THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE, for example, Mernissi related scepticism towards a Hadith to an incident at the local Moroccan grocer’s when she was ‘silenced, defeated and furious […] felt the urgent need to inform [herself] about this Hadith and to search out the text where it is mentioned.’ Her presentation of early Islamic history in a public speech was opposed by ‘a Pakistani editor of an Islamic journal in London,’ (no further specification given) questioning her on her sources. She provided him with a list in Arabic, which he could not decipher due to lacking language skills.

In THE FORGOTTEN QUEENS OF ISLAM, Mernissi set out to ‘demystify history’, to provide information through extensive references, and to prevent misogynist use of history in the contemporary world. This motive is presented more poetically in THE VEIL AND THE MALE ELITE as ‘lift[ing] the veils with which our contemporaries disguise the past in order to dim our present’ and finding a ‘fabulous wind that will swell our sails and send us gliding toward new worlds.’

In this book, Mernissi maintained that women’s participation was controversial but not forbidden. More specifically in relation to critique of a particular Hadith, she stated that ‘nothing bans me, as a Muslim woman, from making a double investigation – historical and methodological – of this Hadith and its author, and especially of the conditions in which it was first put to use. Who uttered this Hadith, where, when, why and to whom?’

Concerning methodology, Mernissi writes: ‘[…] for each Hadith, it is necessary to check the identity of the Companion of the Prophet who uttered it, and in what circumstances and with what objective in mind, as well as the chain of people who passed it along.’ In this context, she also stated that ‘the believing reader has the right to have all the pertinent information about the source of the Hadith and the claim of its transmitters, so that he or she can continually judge whether they are worthy of credence or not’.

With Roberta Mazzanti, Giunti.

A recurring topic for Mernissi in both books and articles was Scheherazade. Her article, The Satellite, the Prince, and Scheherazade: The Rise of Women as Communicators in Digital Islam, explores cases in which women take part in online media outlets, while Digital Scheherazades in the Arab World investigates the topics of online activities shifting cultural ways. She mentioned how technology was spreading quickly and analyzes the roles and contributions of women in this movement.

Mernissi wrote extensively about life in public and private spheres. For example, Size 6: The Western Women’s Harem, a chapter from her book, SCHEHERAZADE GOES WEST: Different Cultures, Different Harems, 2002, discusses the repression and pressures Western women face based solely on their physical appearance.

As Civic Society Builder

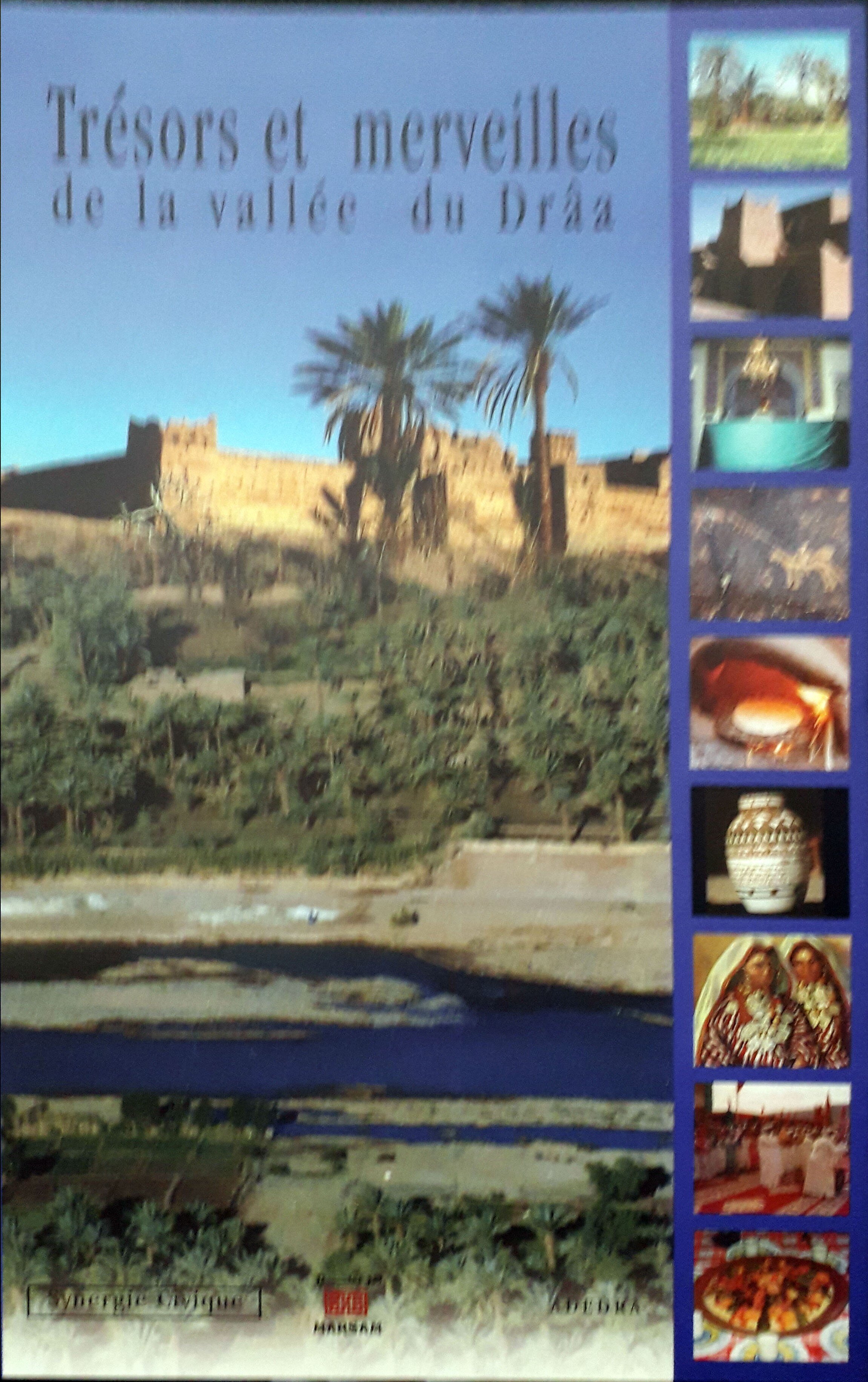

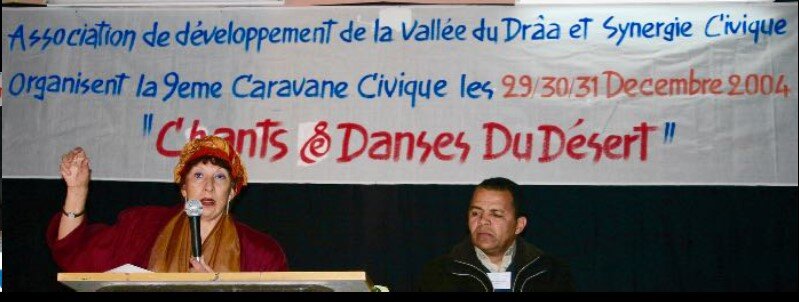

A civic project very close to Fatema Mernissi was Synergie Civique, a project that lasted from 1997-2004.

In l997, Mernissi made a deal with selected NGO leaders: In exchange for conducting writing workshops for their members (musicians, intellectuals, artists, poets, and writers) to increase their communication skills, the members would help Mernissi with her research and provide a bridge between people in rural and urban areas and the cultural world.. The NGOs involved all were representatives of newly self-confident citizens who believed in their capacity to transform the world via focused communication. She helped NGOs and groups to write and publish collective books. Three of the books published under the direction of Fatema Mernissi are:

Marsam, 2004

Marsam, 2005

Marsam, 2012

In the summer of 2005, Fatema Mernissi and Najia Boudali, a geology professor at the university in Casablanca, rented a jeep and driver in search of the Berber women weavers creating the magic carpets full of ancient symbols, vibrant colors, and bold designs that were so high in demand by collectors all over the world. They spent several days in villages around Taznakht, following desert roads and driving up mountain paths. Some of the weavers were old friends Fatema had interviewed more than twenty years earlier. Their children had grown and a few of the daughters and granddaughters had joined their mothers weaving carpets. The houses were the same, but now they all had satellite dishes and cell phones and there was a cyber café in the center of Taznakht. The women weavers were connected to the world and some of their carpets were on websites international buyers had established, and the rug merchants from Marrakech and other parts of Morocco still came regularly to the weekly souk in Taznakht to buy what the local dealers did not take for their tourist shops. Fatema’s and Najia’s dream project was to save some of the best and oldest carpets in a series of family museums. There visitors could see wonderful old carpets on the walls and also choose directly from the weavers’ family those on sale. Much of the profit would stay in the families. It was the latest grassroots project of the “Caravane Civique”. Fatema and Najia Boudali were part of the driving force of this little known group of active intellectuals advancing civil society at home and reducing the flow of migrants looking for work in Europe. Fatema was looking beyond the immediate project of family museums, websites, exhibits abroad and profit for the weavers’ families: she was searching for connections and links to the ancient symbols and patterns embedded in the unconscious of the artist weavers and the attraction of their carpets to the sophisticated collectors in the big cities around the globe. Fatema’s unique interview talents and her rapport with the weavers and their families made the often shy women into true collaborators when proudly posing with their carpets in front of the digital camera. See Gallery for photos.

Six years earlier, in 1999, Fatema Mernissi started the Caravane Civique together with Jamila Hassoune. After listening to the Moroccan bookseller and community entrepeneur dream about a bringing more books into rural areas, Mernissi said, “In 1001 Nights, flying carpets are normal. Me, I dream about a flying library.” Hassoune had started her first Caravane du Livre in 1996, taking cartons of books to rural schools in Morocco’s High Atlas mountains. In 1999, the first Caravane Civique was inaugurated.

The Caravane Civique always included writers, artists, educators, foreign editors and activists, photographers, doctors, and lawyers. Jamila Hassoune still undertakes expeditions - now called again Caravane du Livre - into remote Moroccan mountain villages or distant oases, all addressing her wish to provide contact between young people there with writers, artists, and journalists from metropolitan areas. the caravanes use primarily books, but also movies, plays, and new technologies. For information about the 2020 Caravane du Livre check Hassoune’s website www.jamilahassoune.com

For further reading about Fatema Mernissi, please visit her wikipedia pages.